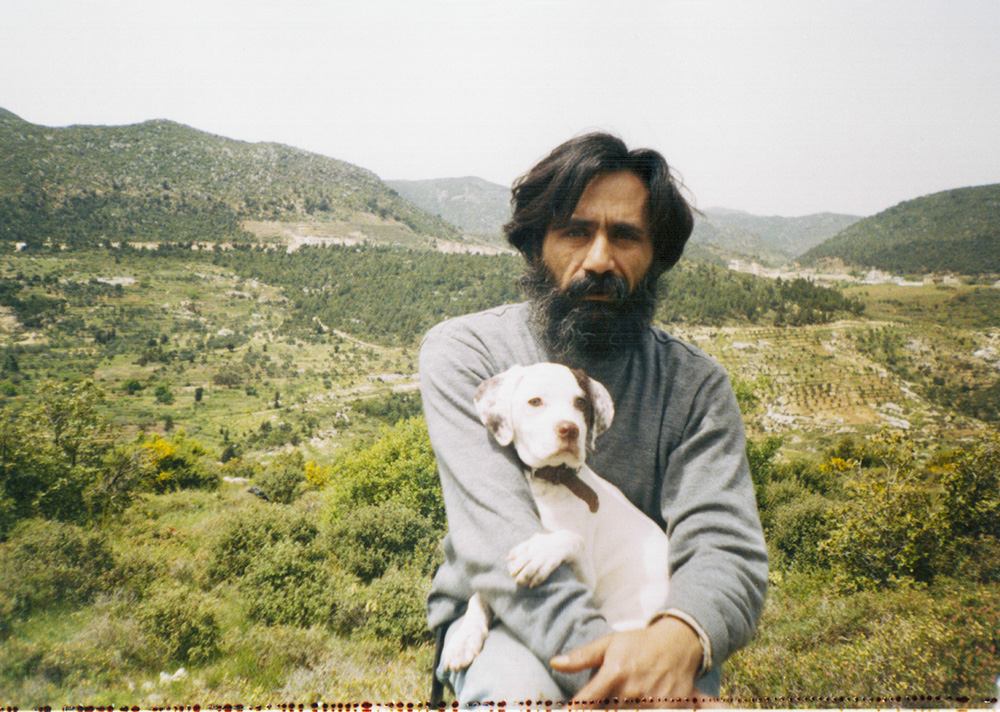

His name is Ahmed. He tells me that he was fully devoted to the revolution right from the first protest, that he was at every march right up until a sniper shot him, that the bullet entered his mouth and lodged itself against his spinal column. He tells me that his mother saved his life by managing to convince an underground surgeon to operate on him. He tells me about his arrest, prison, solitary confinement, with no news of his family for over a year, his trial, his sentence, then his release, his life in hiding once again, his escape from the country.

He comes from a town that has been under siege of the regime’s army for four years. The building where he lived with his family was bombed. Like most of the buildings in the town, it crumbled. They lost everything.

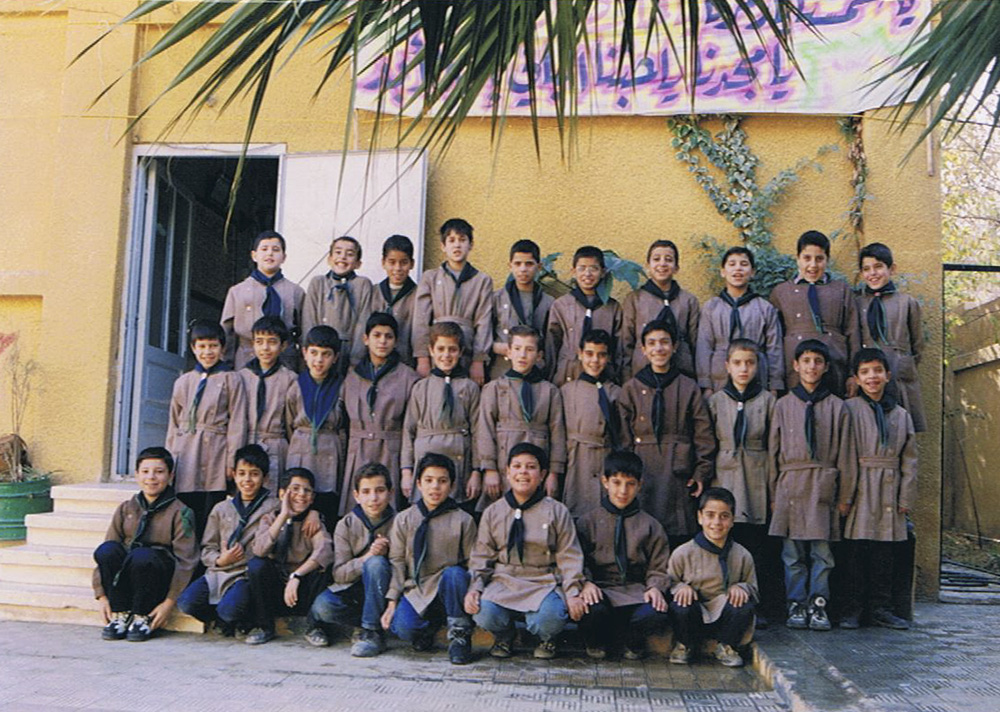

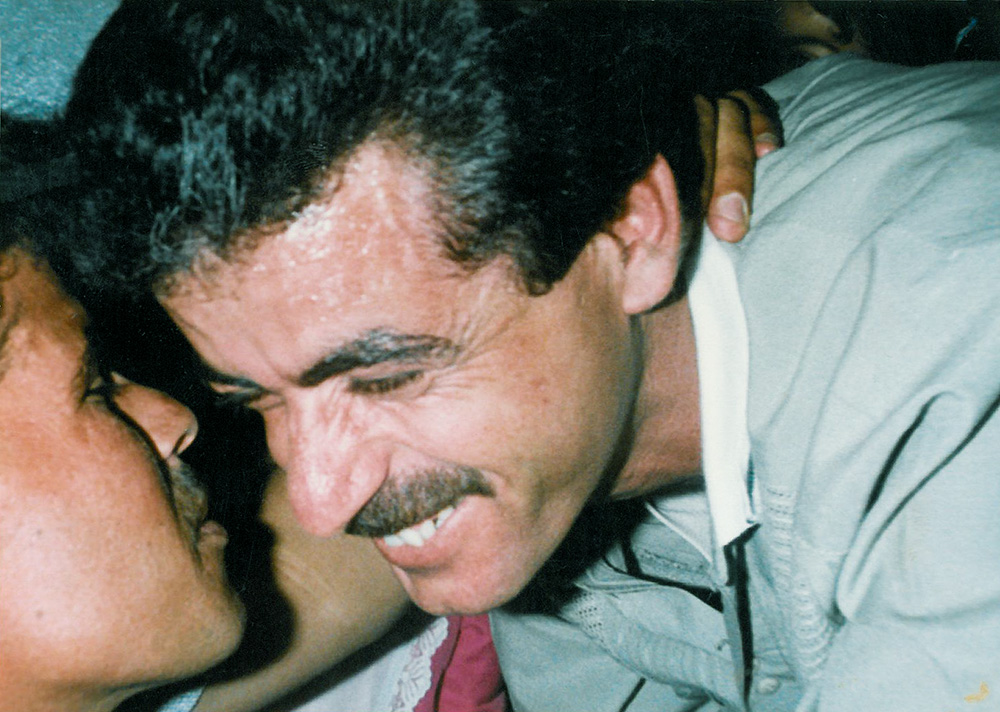

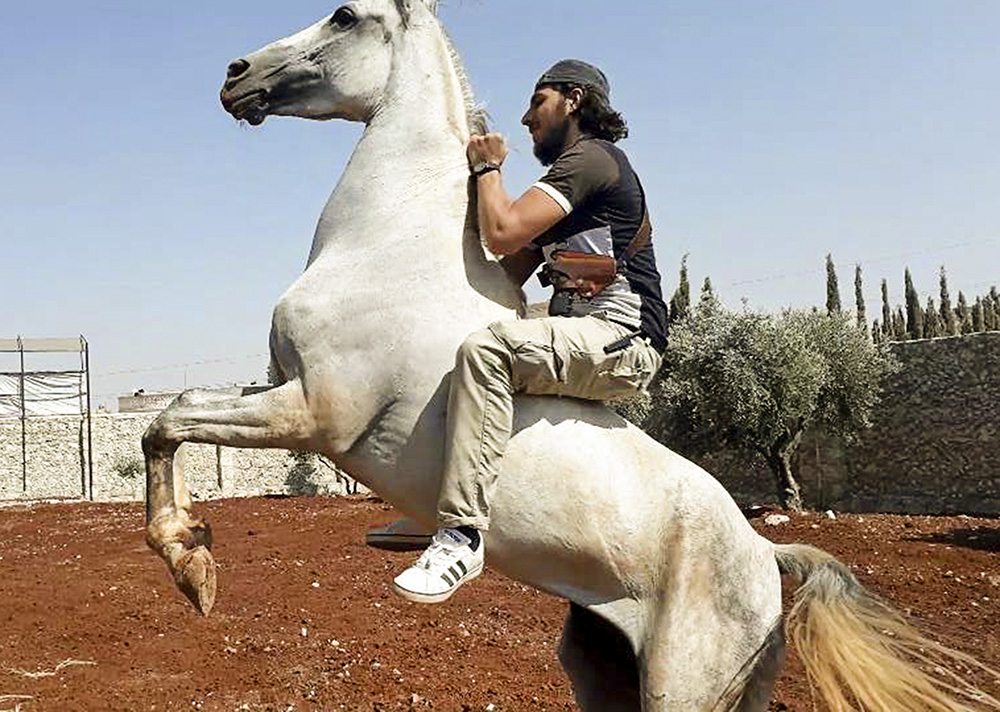

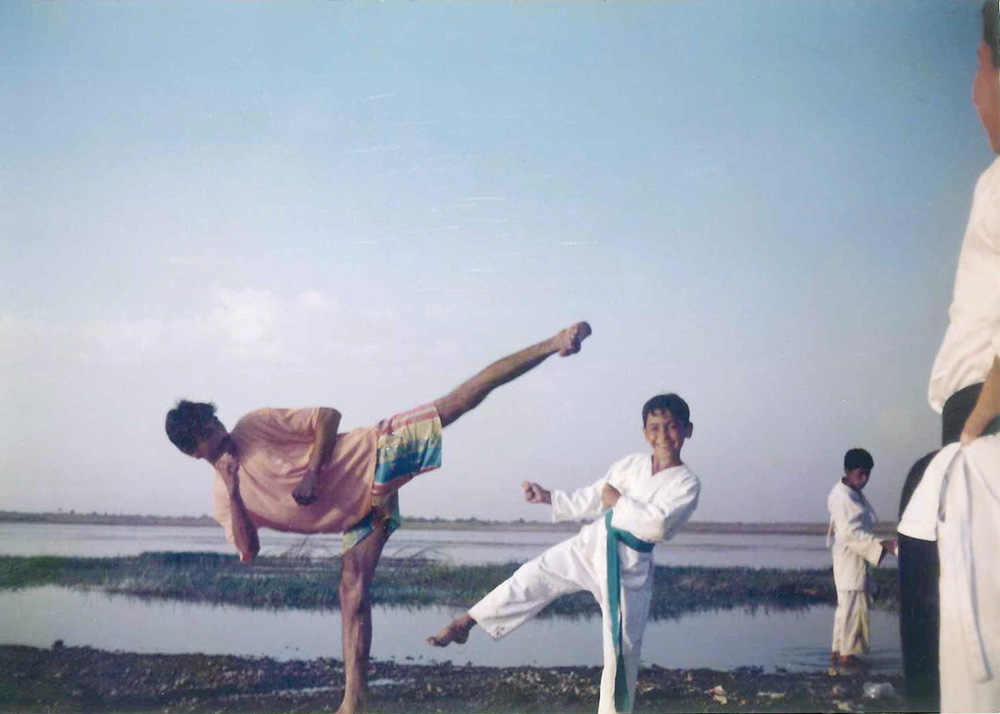

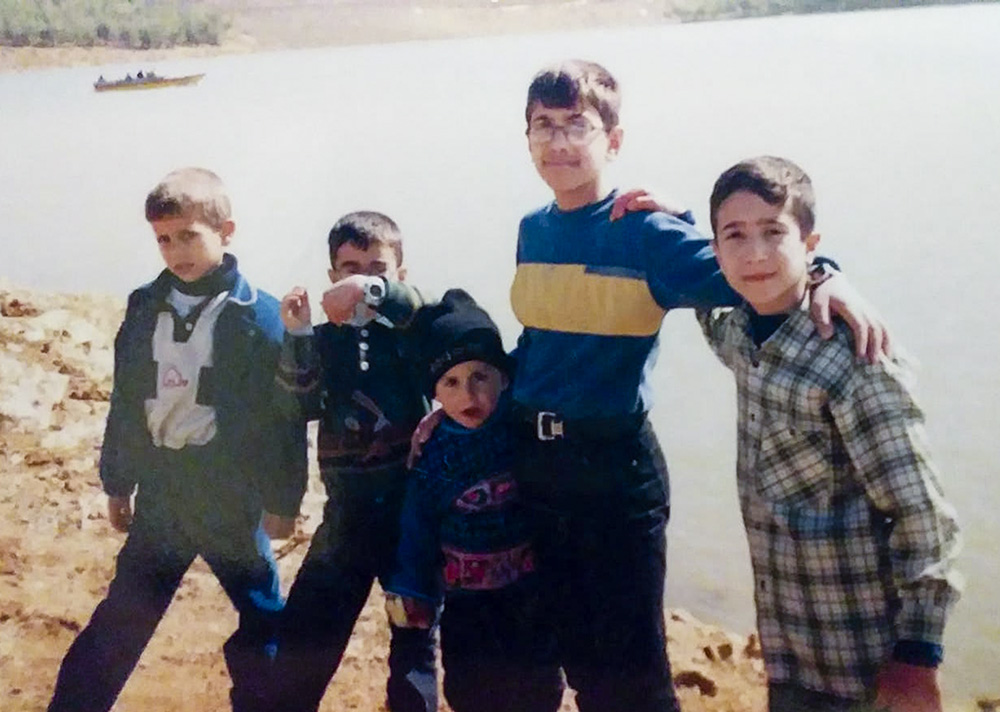

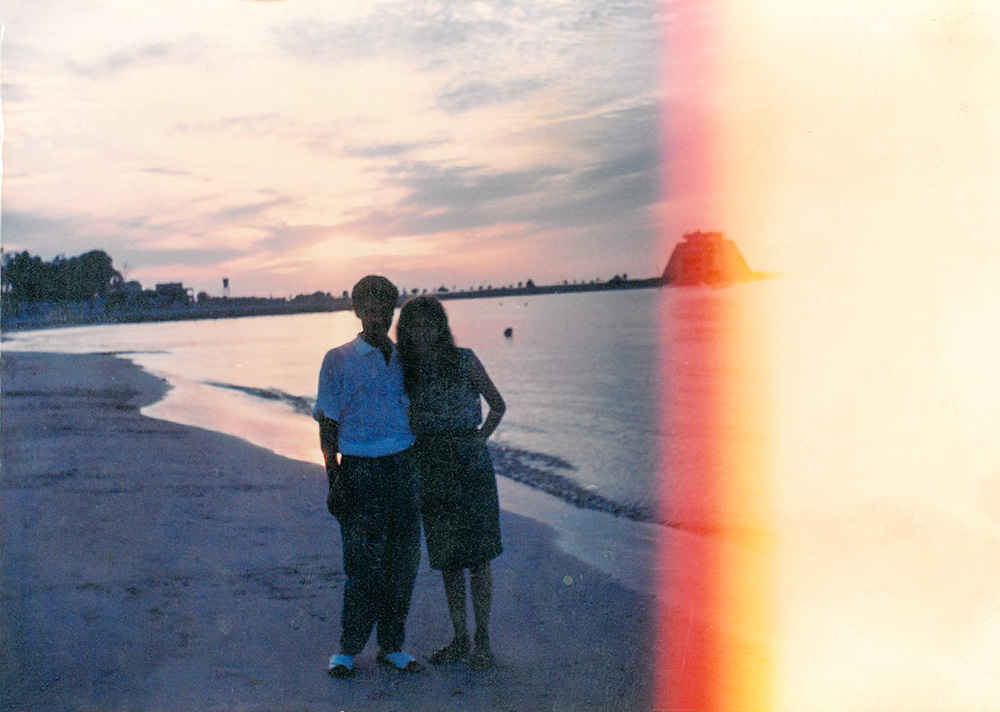

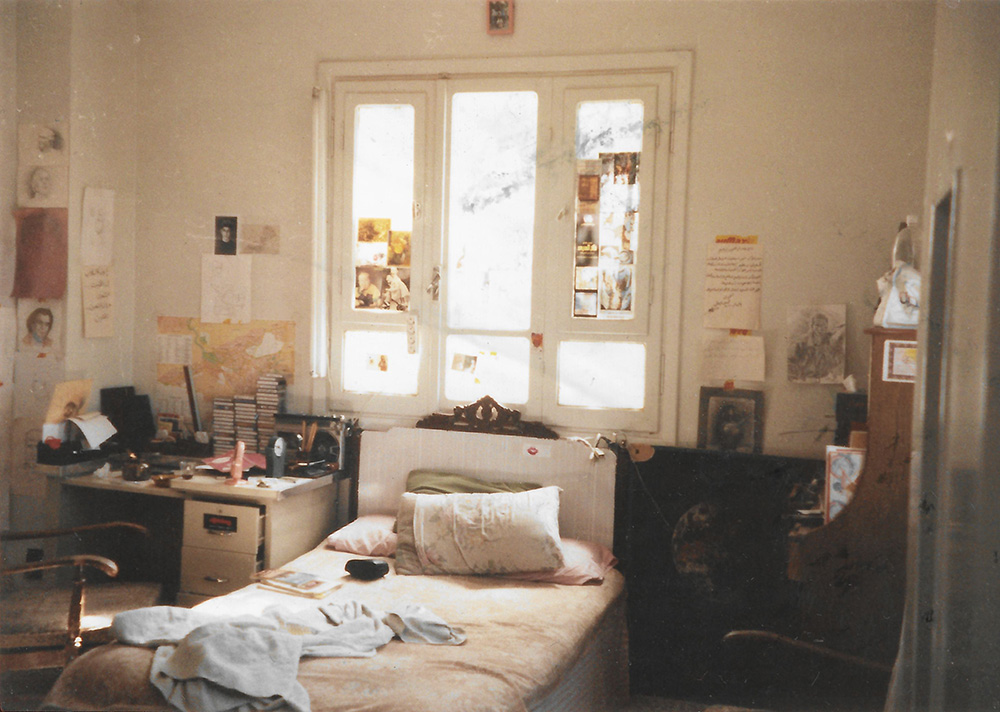

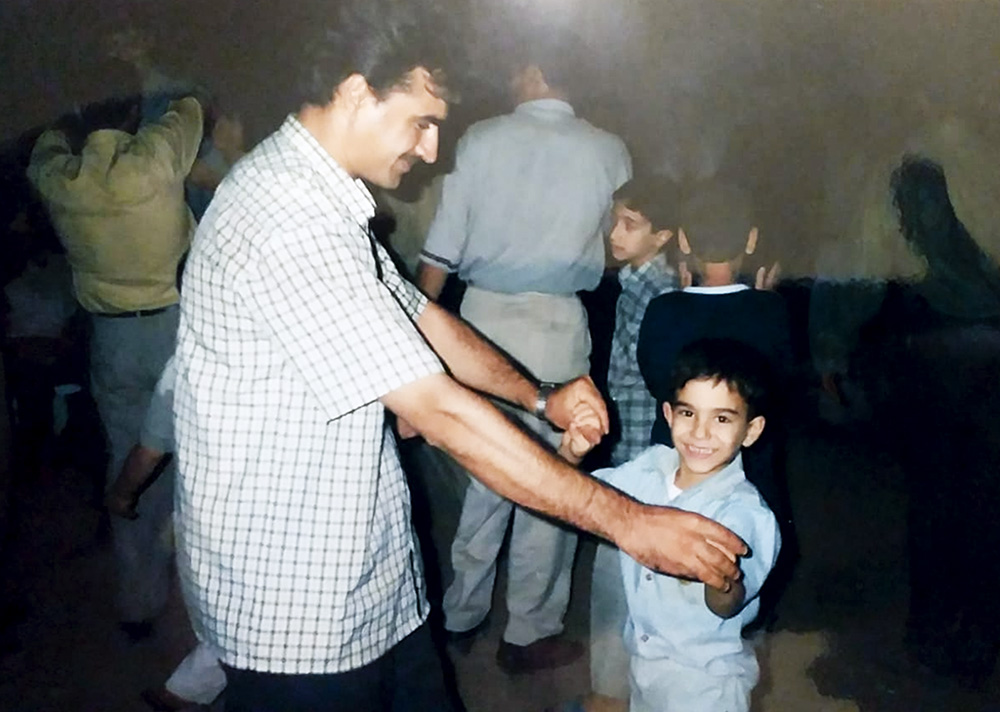

He still has some photos he took before the war with his first digital camera and his cell phone, photos that he saved, scattered on his computer’s hard drive. There is the school trip to Palmyra, holidays at the seaside in Latakia, rides in his first car, the trip with his friends to the North of the country, the impact of bullets on the bodywork after the first demonstrations, the barbecue near the river at a time when he was already being pursued by the security forces. I ask him what happened to his friends. On one group photo, he points out the ones who were arrested, the ones who made it out of prison and the ones who are still inside, the ones who have disappeared and the ones who are dead.